The oldest known sport in the world, played a millennia before the first Greek Olympic Games, is being revived.

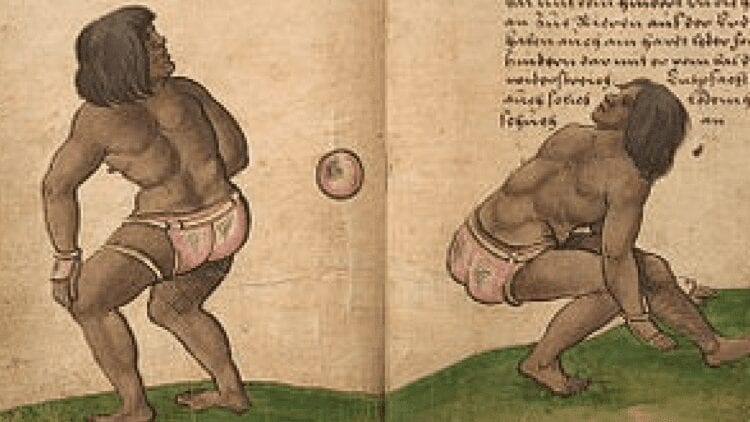

In this bizarre-looking game, teams of four use only their hips to control the ball, juggling it in the air or sliding to tackle it on the ground. Yes, with their hips.

The aim of the game is to control the ball and keep it in the field of play.

The game is known universally today as “ulama,” and it’s played with a large, hard rubber ball that weighs 4.4 pounds. Its precursor is referred to in history books as the “Mesoamerican ballgame,” a ritual sport played since 1400 B.C.

Regional variations existed through history, but today’s ulama is a newer, less dangerous version of the sport.

The version played in Belize is based on an ancient form of Mexican ulama and has its own international tournament…

Belize is a regional power in this sport.

Ancient Rules

Ulama was originally rather like racquetball; the stone ballcourts were a later addition.

Some regions allowed hitting the ball with forearms, bats, and stones; others did not.

Archaeologists believe ancient ulama equipment comprised:

- A loincloth and hip guards

- A thick girdle

- Kneepads

- A type of garter

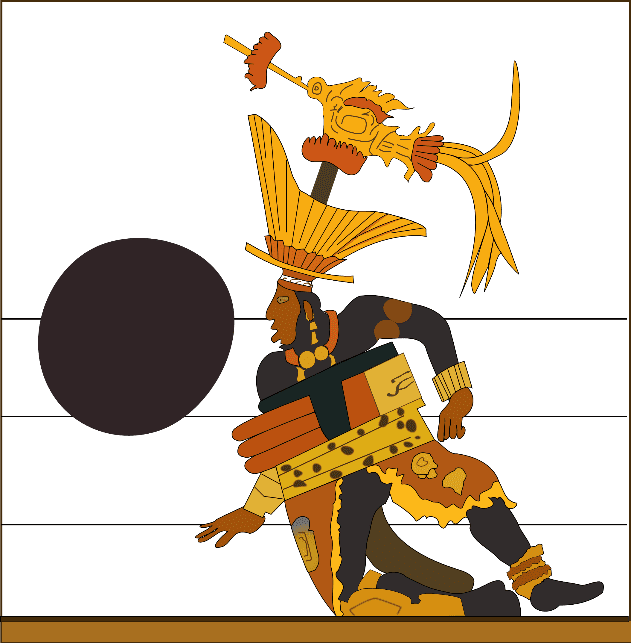

- Elaborate headdresses and helmets.

Some cultures combined human sacrifice with the game—usually the losing team being sacrificed for religious purposes.

Depictions of a gentler version of the game played by women and children are found on ruins all over the region.

The sport was played by all the major civilizations in Mesoamerica: Olmec, Aztec, Maya, and many smaller empires. Because it was played over a vast area, the game has many names: pok ta pok, ollamaliztli, pitz, tlachtli, and more.

History

The game started in the Olmec heartland along the Gulf of Mexico, a lowland region of Mexico where rubber trees grow. “Olmec” is actually Aztec for “rubber people,” named by their successors for their knowledge and use of rubber.

Ulama balls have been found beside ritual offerings to the gods in temples and grave sites across the region.

Around 1000 B.C., the Olmec moved into Central Mexico, bringing the game with them.

By 300 B.C. their game, ollamaliztli, had become widespread throughout Mesoamerica.

The hip version of the sport dominated, but other versions were played with rackets, bats, and different gear and protective equipment with different pitches and rules.

Even without human sacrifice, the game was brutal because of heavy player contact and the impact of the ball.

If the ball hit a player in the head, throat, or stomach, the game could be deadly.

Get Your Free Belize Report Today!

Simply enter your email address below and we'll send you our FREE REPORT – Discover Belize: Reef, Ruins, Rivers, And Rain Forest… Plus Easy Residency And Tax-Free Living

The Maya And The Aztec

The Maya were the first to introduce wall stone rings at either end of the court.

A decisive victory was won if the ball went through the ring at the end of the court.

We know that Aztec players lost a point if they let the ball bounce twice.

The conquistadors tell us that the hips of Maya and Aztec ulama players were perpetually bruised, some so bad that they had to be lanced open.

While evidence of what was worn during the games can only be gleaned from hieroglyphics, sculptures, and carvings (as the leather gear has long rotted), many of the rubber balls survived.

Courts Old And New

Over 1,300 Mesoamerican ballcourts have been identified to date all over the Americas, and more are found every year.

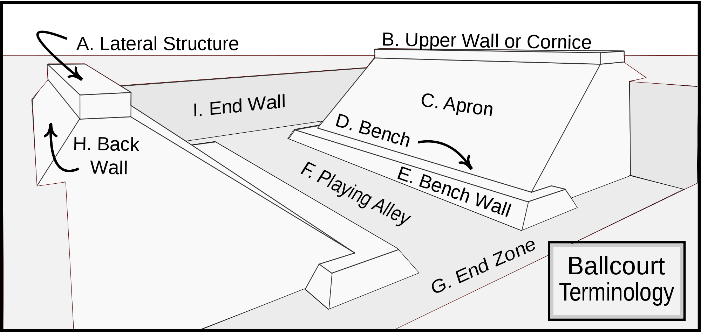

The courts were long, narrow alleys flanked by sloping horizontal walls that were plastered and brightly painted.

Early courts were open-ended; later ones were enclosed.

Courts were usually four times longer than wide, but their sizes varied immensely. For example, the Great Ball Court of Chichén Itzá was 96.5 by 30 meters (316 by 96 feet).

By the early pre-classical period the stone courts fell out of favor. This is how the game is played today.

Cultural Significance

Games were played at significant events and held ritual connotations.

As a way to diffuse conflicts without war, games were also used to decide the outcomes of inter-kingdom disputes.

Mythology

The Popol Vuh, a K’iche’ Maya religious and mythical narrative, provides an account of how the game of ollamaliztli—with its symbolic reflection of warfare, fertility, and death—came to be.

According to the K’iche’ Maya…

The god Hun Hunahpú and his brother Vucub Hunahpú played ball near the entrance to Xibalbá, the Maya underworld.

The lords of the underworld grew annoyed at the game’s noise, so two of the higher gods made the players fall asleep and captured them.

Hun Hunahpú was sacrificed and his decapitated head was hung on a tree, which became the first calabash, or gourd, tree.

Hun Hunahpú’s hanging head spat in the palm of the hand of a passing goddess, Ixquic, who conceived the legendary hero twins of the Maya, Ixbalanqué and Hunahpú.

Many years later, the boisterous hero twins found their godfather’s ball gear at home and started playing loudly, to the continued annoyance of their father’s killers, Hun Came and Vucub Came. A punishing series of challenge games ensued between them, as the higher underworld gods tried to get rid of the noise once and for all.

In one game, Ixbalanqué loses his head to a bat swing so his brother replaces it with a squash until the gods stop playing with Ixbalanqué’s head.

The twins eventually win the games with the gods after many toils.

Human Sacrifice

The practice of human sacrifice only raised its visage late in the classical period, during the apogee of the Maya civilization and was only evident in the Maya and Veracruz cultures.

In one depiction, a winning team at Chichén Itzá (circa 900 to 1200 A.D.) is shown being sacrificed. You can also find drawings of decapitations as well as tzompantli, skull racks where severed heads were displayed.

Morbid speculation suggests that the skulls were used as balls for play, but modern doctors think this was improbable due to the unwieldy and difficult nature of controlling such an unbalanced projectile.

The Game Today

Nowadays, the game is played on a flat area, usually bare earth, measuring 30 by 15 meters.

It involves four players and is similar to net-less volleyball, with two sides to the court. Players pass the ball back and forth between sides until one team fails to return the ball or it goes out of bounds.

In Belize, the Maya reintroduced this game in some villages in 2015 with great success.

The “Pok Ta Pok” team from Yo Creek Village in the Orange Walk District of Belize returned victorious from the second “Juego de Pelota Mesoamericano Ulamaztli” championship held in Teotihuacán, Mexico City, in April last year.

Then, in October 2017, the very same Yo Creek team won the Annual International Mesoamerican Ball Game Competition in Guatemala (the World Cup, essentially) bringing pride to their village and honor to their ancestors.

In Belize, Mexico, Guatemala, and Honduras, organizers and competitors alike are preserving an ancient ancestral tradition.

Con Murphy

Belize Insider